Journeys in Search of Grand Canyon Uranium – Nuance and Apocalypse in the Earth’s Greatest Landscape

I've been interested in nuclear science and technology since I was eight years old. I can still picture the first book that I read on atomic energy that led me down this path. I've previously addressed the subject by painting nuclear research and production facilities associated with the Manhattan Project of World War Two and the Cold War. In 2015, as I began on a new project that would focus on uranium mines and production facilities here on the Colorado Plateau, my focus shifted when I learned about the breccia pipes of the Grand Canyon region. I became fascinated with these vertical subterranean structures and that are essentially unknown outside of the energy and mining industries and a relatively small number of geologists. On the other hand, the mines that access and work these deposits have become highly controversial today.

Since their arrival in North America, Europeans have shown that they view Nature from a highly paradoxical perspective. On the one hand, they profess to revere Nature. They extoll its beauties and virtues in art, music, and literature. It could be easy to believe that people coming from a European background view Nature as a deity, and in some cases this is how it is viewed. On the other hand, wholesale destruction and poisoning of the worldwide ecosystem provides ample evidence to the contrary. Nature is seen as the source of raw materials that have created a society based on the consumption of all manner of products, from food and household items to cars, electronic devices, and so much more. This relationship is a classic example of loving something to death.

In his 1836 painting, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, Thomas Cole provides a visual key for decoding the paradoxical relationship that Euro-Americans have with Nature. Divided into a light side and a dark side, the painting extolls Nature’s beauty and its bounty in a sublime spectacle. In the sunlit river bottom scenes of pastoral development and the boats traveling on the Connecticut River convey peace and prosperity. Nature brought under control for the benefit of humanity. While the seeds of the wilderness movement were sown by Transcendentalists, the prevailing sentiment at the time was that land was only useful when put to productive use, revealed by the deforested river bottom.

Cole was an early proponent of wilderness for its own sake. In this view, Cole’s wilderness is not only threatening, with its passing storm and storm blasted trees, but it is threatened by the development in the valley below. To underscore this quandary, the painter provides another subtle intimation. Across the valley, on the far hillside, logging scars in the trees seem to loosely form Hebrew letters. From the earthly perspective it reads as Noah (נֹ֫חַ). If viewed from Heaven, the word Shaddai ( אֵל Almighty) is formed. It is reverence with a warning. Cole’s paintings, and those of the Hudson River School at large, educated Americans on the reverent appreciation of Nature as an aesthetic pastime.

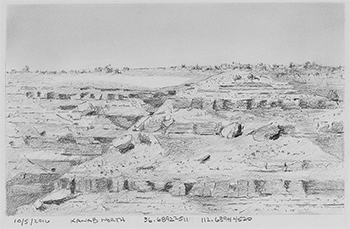

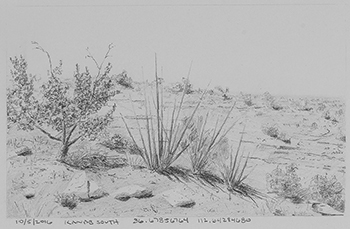

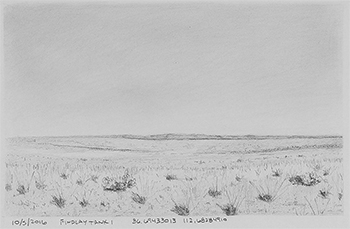

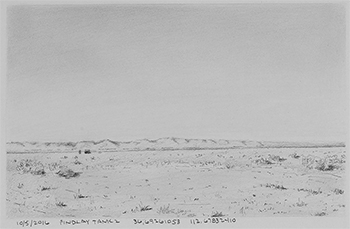

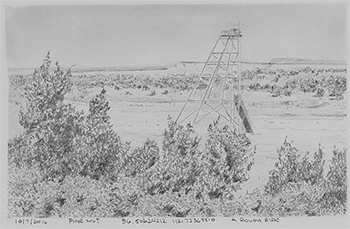

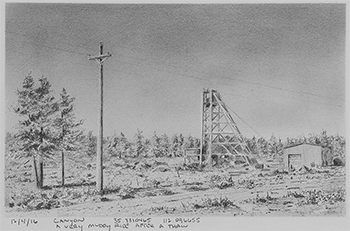

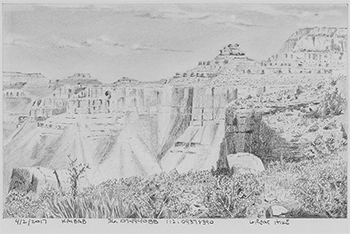

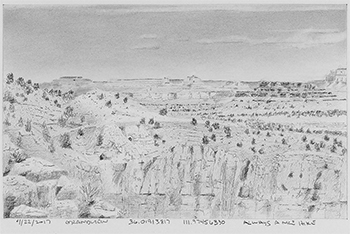

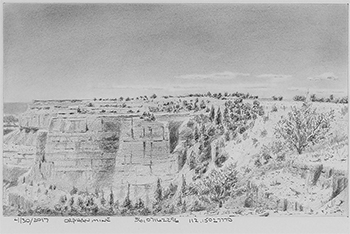

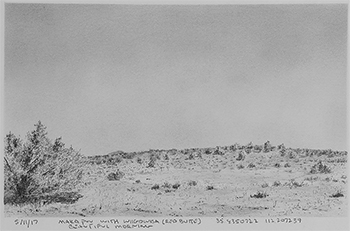

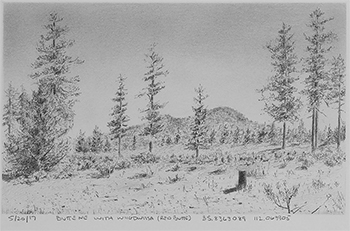

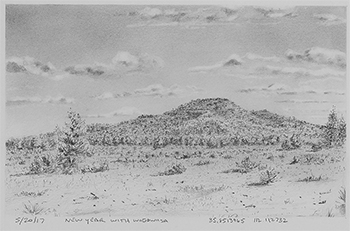

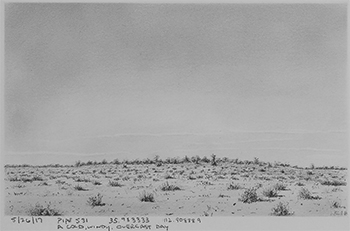

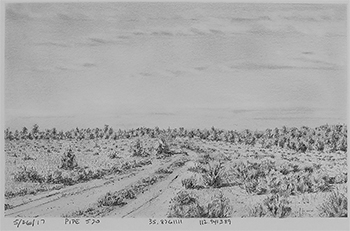

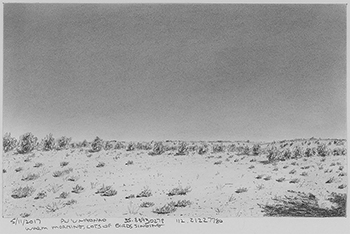

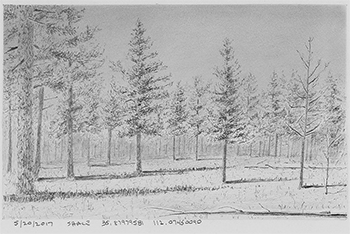

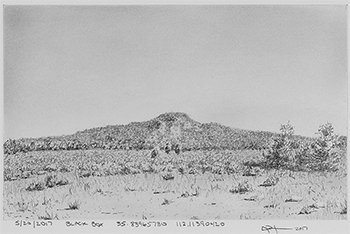

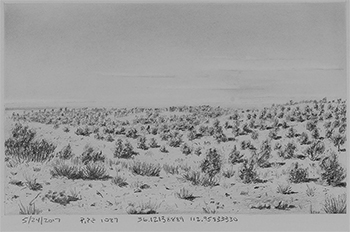

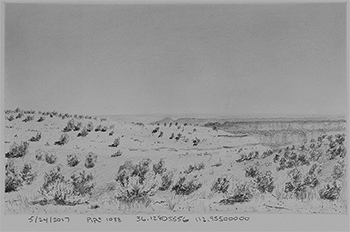

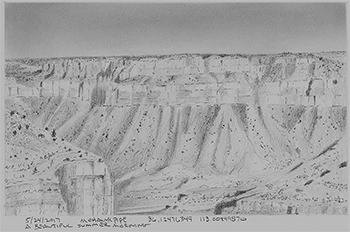

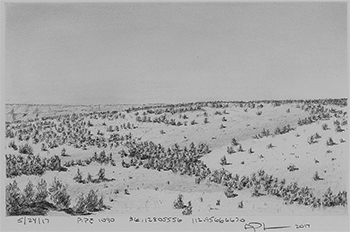

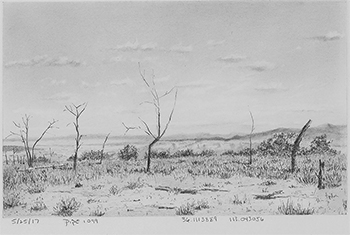

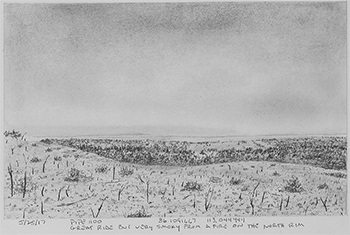

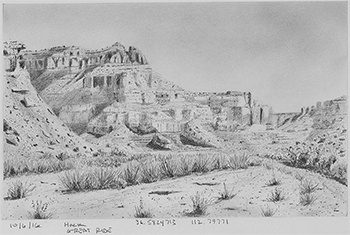

I set out to explore the breccia pipes of the Grand Canyon region on bicycle and on foot in order to fully understand the landscape and geography in which they are located. A few, such as the site of the former Orphan Mine at the South Rim of Grand Canyon are very accessible. Others, such as pipe 493 in the western Grand Canyon, are exquisitely remote. To date, I have ridden 230 miles on my mountain bike and hiked many miles to visit 51 pipes and mine sites. I do drawings in the field and photograph the sites. Back in the studio I produce finished drawings. My approach, inspired by Ed Rushe’s photographs of apartment buildings and parking lots in 1960s Los Angeles, is one of neutrality. There is no celebration of the Sublime or of Romantic overindulgence.

Few of the breccia pipes are visible. Their veiled and obscure nature is one of their characteristics that attracts me. Some are visible, revealed in side canyons where the strata around them has eroded away. In the most dramatic examples, this leaves the harder core of the pipe (the breccia) revealed as a free-standing vertical column. In many other cases, where the pipes are found in the surrounding countryside, all that may be visible is a shallow depression caused by the collapsed layers below. The depression may be seen as a large, somewhat barren circular area that will become a large mud puddle when it rains.

Grand Canyon. A place that many people from around the world recognize as one of Earth’s great landscapes and an illustration of the vastness of time and change on Earth.

Uranium. Despite their limited knowledge of the element and the science, just mention of the word “uranium” will create anxiety for many people. It is a powerful element that offers great benefits for humanity, and a far greater threat.

Each of these artifacts of Nature defy our daily understanding of our existence and together they present an intriguing paradox.

Each year, Grand Canyon is visited by millions of travelers seeking its beauty and tranquility. Of these visitors, a very few realize that uranium has been mined in Grand Canyon, and within the boundaries of the national park, from the 1950s until 1969. Far fewer realize that within a very short distance of where they stand and take in the beauty of the Canyon lie richly concentrated deposits of uranium. One has to imagine that if every visitor knew of this hidden, potentially highly toxic, element bound up in that landscape, many would have a very different experience standing on the rim of the Canyon or hiking along its popular trails. It is a sublime landscape and one that harbors images of Gotterdammerung.

Grand Canyon is the ultimate Sublime landscape. It is one of the ultimate Romantic concepts as its meaning is synthesized from both art and science. The first paintings and photographs of Grand Canyon began to be widely distributed in the 1870s and by the 1880s it had become a destination for adventurous travelers. With the coming of the Santa Fe Railroad in 1903, the general public began to arrive. The Santa Fe sold Grand Canyon as the must-see destination for every traveler and a large audience was eager to indulge in the Canyon’s seductive beauty. They had been prepped and educated by the artists of the Hudson River School, and in particular by one of its later proponents, Thomas Moran, known for his early paintings of the canyon; by John Wesley Powell, first to explore its depths and to write about his harrowing exploration; and by Clarence Dutton, the field director of Powell’s ten year geographical and geological survey of the region and the first to write a scientific monograph on the region. Dutton emphasized the immensity of the largely unknown landscape and made it clear that knowing it was possible only with time and study.

It is interesting to note that the coming of the first tourists by railroad to Grand Canyon in 1903 corresponds to Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy’s publication of their scientific paper "Law of Radioactive Change" and the rapidly growing field of nuclear physics.

Prospectors and miners began arriving at Grand Canyon in the early 1870s. Despite the extremely rugged topography, within a few years they had explored most of its remote nooks and crannies seeking mineral wealth. They didn’t find much gold or silver but they did find copper and asbestos. Uranium wasn’t identified until the 1940s in the tailings of some of the late 19th century copper mines. It had become highly desirable due to the success of the Manhattan Project of World War II and the increasing desire for nuclear weapons brought about by the Cold War. By the 1970s, there were thousands of staked claims in the region surrounding the Canyon.

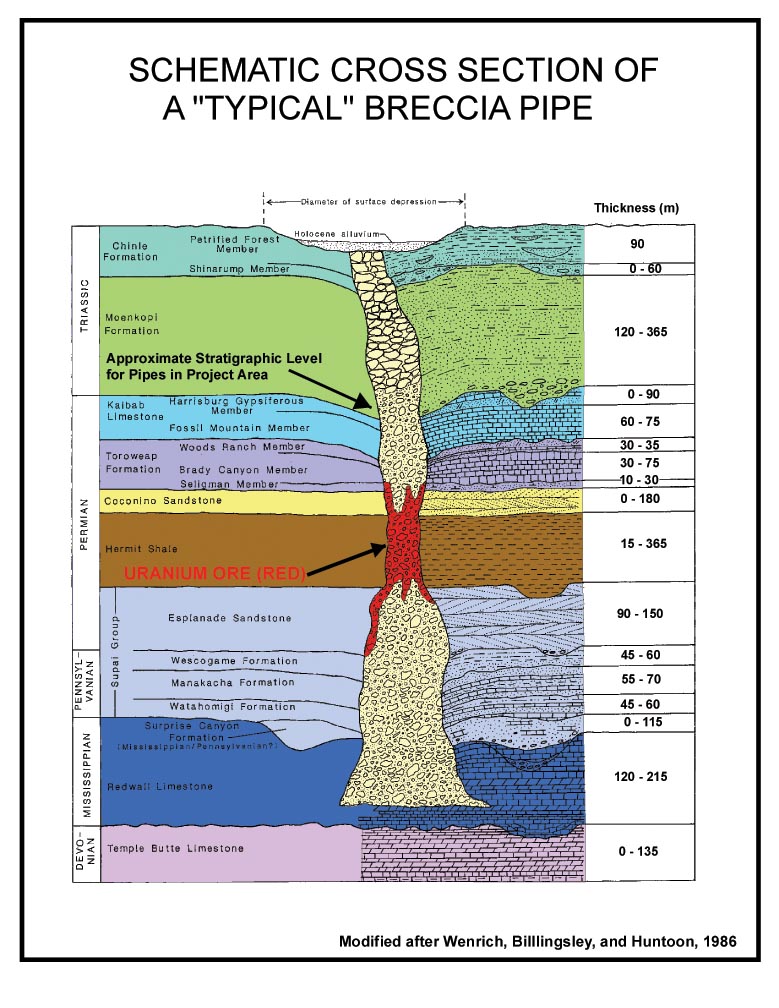

In the Grand Canyon region, uranium is associated with minerals found in geological structures called breccia pipes. The Italian origin of the term means either "loose gravel" or "stone made by cemented gravel.” Nineteenth century copper mines in Grand Canyon extracted copper ore from breccia pipes, though the miners didn’t recognize the larger geological structure or meaning of the pipes. Breccia pipes in northwestern Arizona are the result of the dissolution of the Redwall Limestone (one of the most prominent cliff-forming layers in Grand Canyon), forming caverns, some of which collapsed, leading to the successive collapse of the overlying strata. This collapse produced steep-walled, pipe (or chimney) like bodies that were filled with small to house-size blocks of rock from the collapsed upper strata and bounded by a steeply dipping ring-like fracture zone circling the pipe. Dissolution of the Redwall Limestone began during the Late Mississippian (approximately 330 million years ago), creating an extensive karst terrain characterized by sinkholes, caves, and extensive underground drainages. As a result, in cross-section Grand Canyon might convey an image not unlike Swiss cheese.

There are nearly 1,300 breccia pipes and other related collapse structures in and around Grand Canyon. Not all contain uranium, but many do and only a small number of them have been fully surveyed and assessed. It is in these large vertical structures, (30 – 70 meters in diameter and between, roughly 800 – 980 meters deep) that uranium, along with other minerals, was deposited by ground water. The breccia pipes are natural conduits for ground water and one of the implications for mining uranium in this region with its intricately intermingled caverns and groundwater system is the pollution of water supplies for Native Americans living in and around Grand Canyon, most notably the Havasupai, Hualapai, and Navajo peoples.

There are nearly 1,300 breccia pipes and other related collapse structures in and around Grand Canyon. Not all contain uranium, but many do and only a small number of them have been fully surveyed and assessed. It is in these large vertical structures, (30 – 70 meters in diameter and between, roughly 800 – 980 meters deep) that uranium, along with other minerals, was deposited by ground water. The breccia pipes are natural conduits for ground water and one of the implications for mining uranium in this region with its intricately intermingled caverns and groundwater system is the pollution of water supplies for Native Americans living in and around Grand Canyon, most notably the Havasupai, Hualapai, and Navajo peoples.

Since 1951, twelve mines have produced more than 1,471,942 tons of uranium ore that produced more than 19,000 pounds of U3O8 (Triuranium octoxide is a popular form of partially refined uranium that is shipped between mills and refineries). Eight of these mines were located below the North and South Rims of the Canyon and inside the current boundaries of the national park, though (as the result of expanded boundaries in the 1970s) most were not within the national park when they were operational.

To the general public, uranium represents an intense—and often misunderstood—threat. Uranium in its natural state, as found in breccia pipes, emits relatively low levels of radioactivity and is not particularly dangerous. However, news reports of nuclear accidents like the 2011 catastrophe at Fukishima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan, the historical photographs of the two atomic weapons dropped on Japan in 1945, and subsequent atomic bomb tests depict scenes of apocalyptic magnitude.

It has been extremely rewarding to visit the breccia pipes that I have and to experience them within the greater landscape context, knowing that they extend thousands of feet below the surface and harbor a powerful. In contrast with the great dynamic nature of Grand Canyon as a geological and geographical feature and a popular subject of art for more than 100 years, I have sought the subtle and nuanced expression of geological features that are largely benign, unknown, and unseen, yet capable of social and environmental violence of the highest order.

For more information and details see the associated story map here.

Home

Contact information

©2020 Alan Petersen